You are Awesome

You

Are

Awesome

7 Things This Book will Teach You

- The single word that keeps your options open after failure (Page 23)

- How the spotlight effect fools your brain into thinking poorly of yourself (Page 51)

- What every commencement speech gets wrong (Page 147)

- 3 ways to dramatically accelerate ability to learn and adapt (Page 151)

- The 2-minute morning practice that helps eliminate worry (Page 181)

- The reason you shouldn’t buy the $5 million Manhattan condo (Page 201)

- Why you need an Untouchable Day (and how to get one) (Page 223)

Sample Pages

From the Book

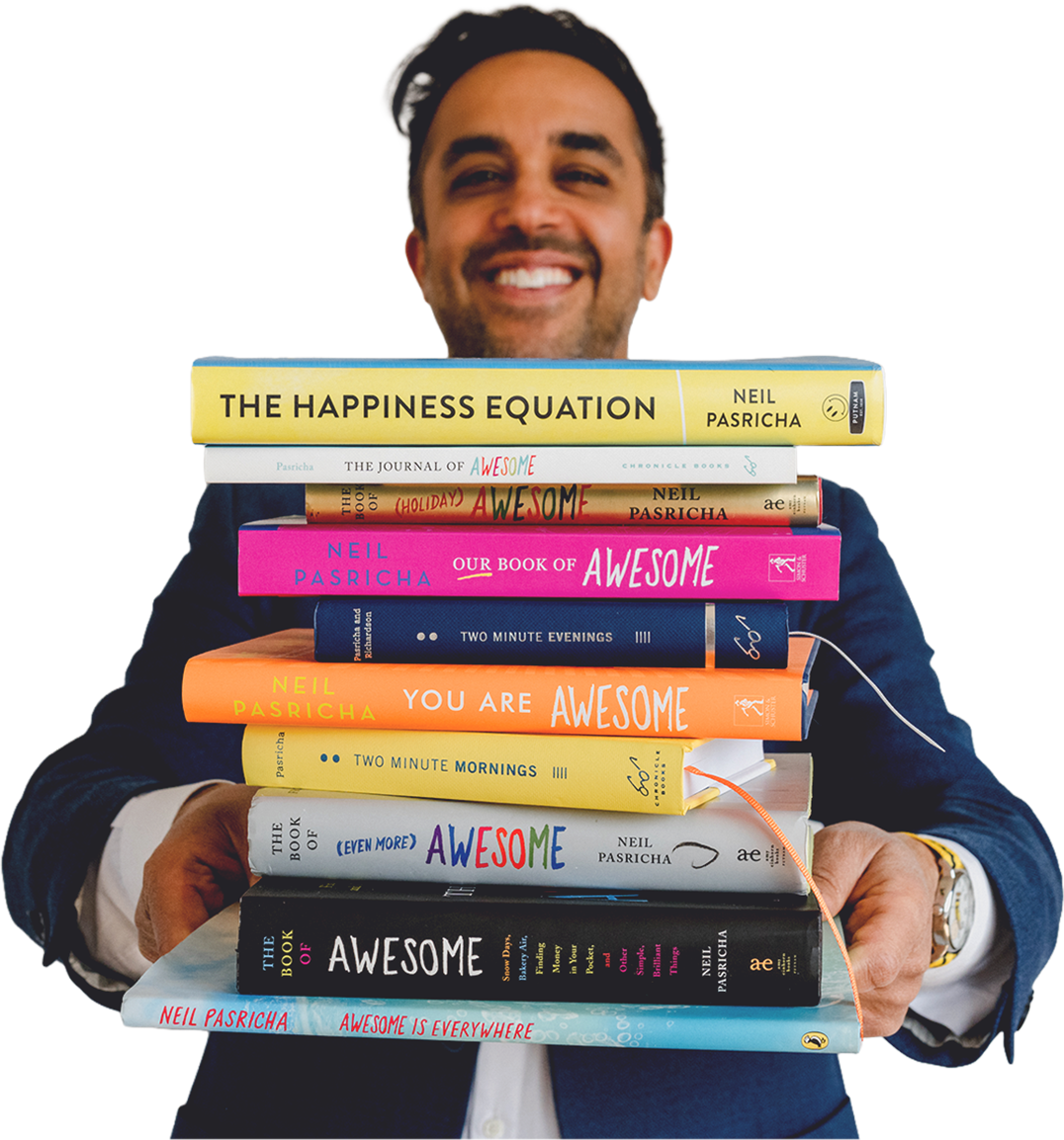

This book is a continuation of Neil’s multi-decade writing on living an intentional life.

CLICK ON A COVER TO LEARN MORE:

![]() There are few things more certain in all aspects of life than set backs!”

There are few things more certain in all aspects of life than set backs!”

Finding the resilience to, not just cope, but take these in your stride and ultimately learn from them is a critical skill in today’s unpredictable world. Neil’s book provides an invaluable framework and toolkit. Full of practical ideas and suggestions, supported by personal anecdotes and stories that bring them to life. Neil has done it again, produced a personal, practical and universal guide to life.”

– DAVID CHEESEWRIGHT

Former President and CEO, Walmart International

![]() I have been through struggle. I have been through loss. And I have had to get stronger.

I have been through struggle. I have been through loss. And I have had to get stronger.

Resilience is a muscle that hurts to build. What would have made it easier? Neil’s words. This book. A recipe for thickening our skin in thin-skinned times.”

– JAMES FREY

author of A Million Little Pieces

![]() Neil was an incredibly quiet, shy, and curious student in my classroom over thirty years ago.

Neil was an incredibly quiet, shy, and curious student in my classroom over thirty years ago.

I have long retired from teaching and am now watching as he becomes the teacher for me and many others. This is a guidebook for those establishing careers and raising families but it’s also for those of us in later years who face a whole new set of challenges. Neil’s enthusiasm for living is truly infectious.”

– MRS. STELLA DORSMAN

Neil’s third-grade teacher

About

Neil Pasricha

Neil Pasricha thinks, writes, and speaks about intentional living.

He is the New York Times bestselling author of ten books and journals, including The Happiness Equation and Two Minute Mornings which together have spent over 200 weeks on bestseller lists and have sold over 2,000,000 copies.

He hosts the award-winning podcast 3 Books, which features live conversations with guests such as Brené Brown, Quentin Tarantino, and David Sedaris.

He gives over fifty speeches a year to audiences such as Harvard, SXSW, and Shopify. Neil has degrees from Harvard University and Queen’s University. He lives in Toronto with his family.

Download the You Are Awesome

Teacher’s Guide

Book

Neil